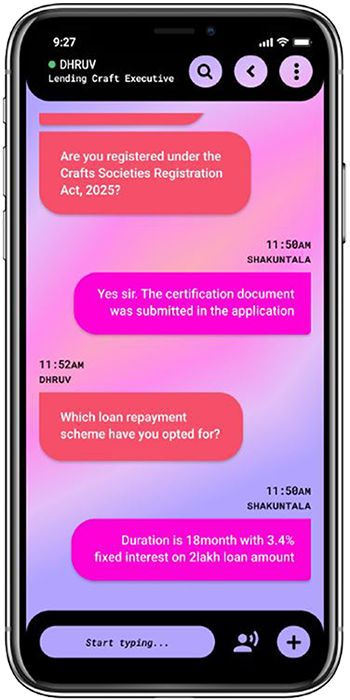

Mohamad Shaid

Adda Karigar

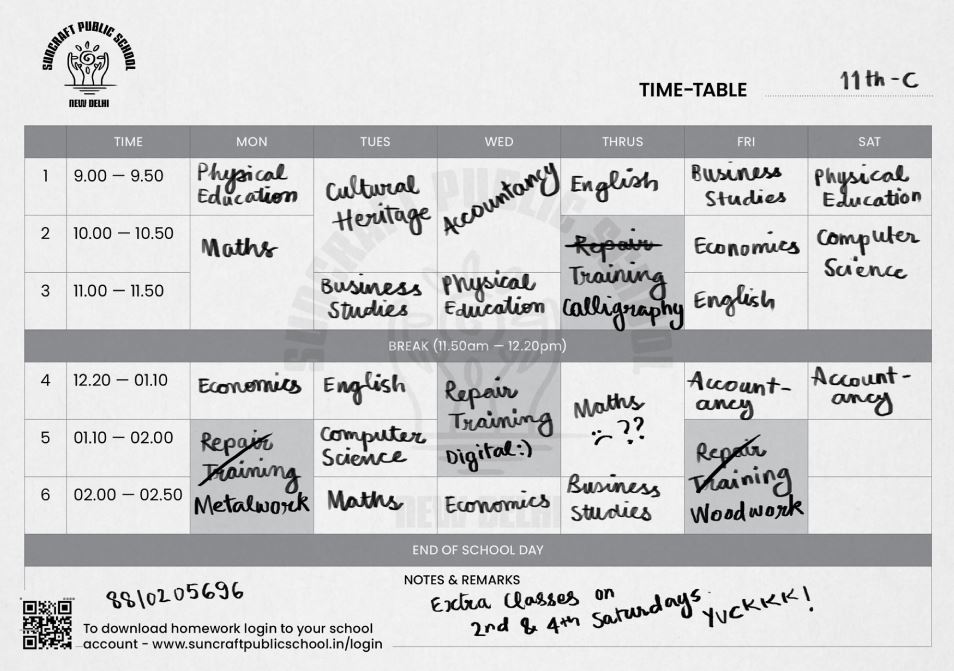

Synchronicity, skills

and sequins

Embroidery remains a cherished Indian textile tradition. The precise detailing and fine stitches on Indian attires make it one of the most recognisable and sought-after textile-based craftwork today. The tools used are fairly simple—threads, needles and sequins. Instead, it is the coordinated skill and collaborative spirit of the karigars that bring the intricate designs to life.

Watching Mohammad Shahid and his fellow karigars at work is a captivating sight—their fingers moving deftly across the surface, pushing the needle into the cloth and pulling the thread out to secure the element in place. Each karigar has a specific skill set and signature style. However, when working on the same fabric, these differences dissolve into a synchronised rhythm. The final product is a seamless design that seems to have originated from a single hand.

The process begins by stretching out the fabric on an adda (4-legged wooden frame). Embroidery is always done on a horizontal surface, explained Mohammad Shahid. Drawing on his years of experience working in the field, he said, “If you weave designs on the vertical surface, the fabric gets stretched and ruins the design. And that is why one should always weave on the horizontal surface.”

The karigars sit cross-legged around the adda, with all their tools strewn across the floor. These include curved hooks, needles, sitaras, round-sequins, plastic and glass beads and dabka thread (french wire).

First, the design is traced onto the fabric. The karigars are adept at working with a range of different materials including satin, cotton, net and silk. The fabric is then stretched onto the adda and secured. The embroidery can now begin. Each element is sewn onto the material with absolute precision and accuracy.

Mohammad Shahid learnt the skill of embroidery in Mumbai but shifted to Delhi and has been collaborating with and producing outfits for several designers. Having worked in an export house for many years, he has also spent considerable time working with technological innovations in the field. However, he continues to believe that the smallest details and finest finishes can only be achieved through hand embroidery.

In case you are looking for fine karigari to add a special touch to your next wedding outfit, visit Mohammad Shahid in Delhi.

~